(Image: publicdomainpictures.net)

We practice syllables, slowing stringing together sounds to make simple words. Cat. Mat. Sat. The easy stuff. It’s the beginning of a long journey, the crux of my 5-year-old son’s education. As a mother, a writer, a lover of words, there is an unparalleled thrill in watching my son learn to read, and in helping him along the way.

I write down words and he copies them, reads them back to me, commits them to his expanding memory. Some days we write together—he dictates, I transcribe. When we finish, I read the tales back to him, slowly, as he concentrates on the individual words—memorizing and reading his own stories.

Someday he will write stories all by himself. He will read them too. Stories that will thrill him, stories that will inspire him, stories that will change him, and stories that will bore holes into the soft places inside him.

And on that last note, I am reminded that part of me doesn’t want my son to learn to read.

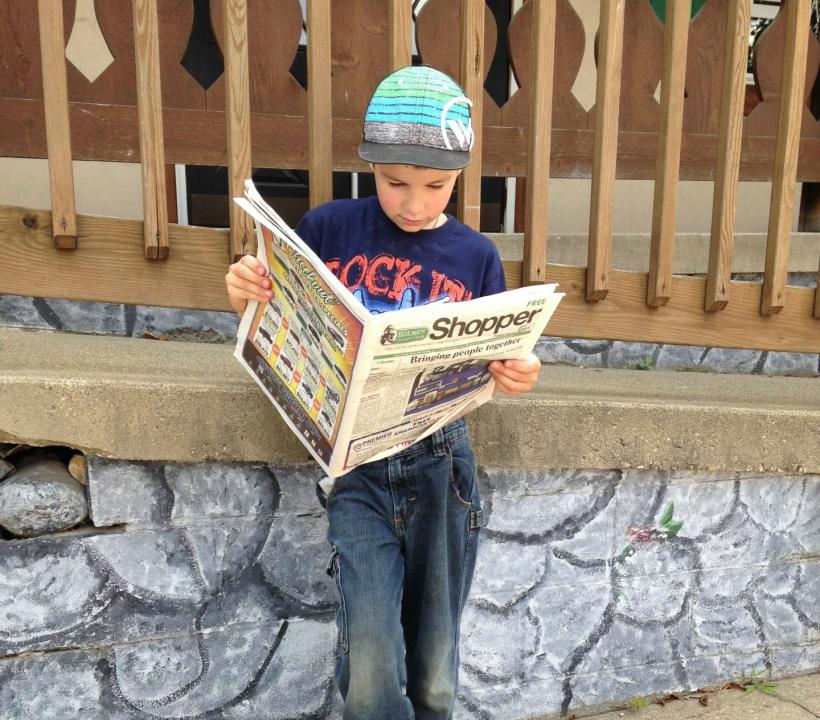

There are many days when he will see a photograph from the news: a boy in a gorilla’s enclosure, a gathering of mourners, a flash of police lights, the face of a criminal whose name I don’t want him to know, a victim whose story I cannot tell without crying. These are the moments I feel grateful that he doesn’t know how to read. For now, he asks me about the things he sees, and trusts my role as the gatekeeper of knowledge.

I want to extend the age of innocence as long as I can, but soon a day will come when I can no longer lie to him about the headlines and images he sees in the news.

“Why is there a picture of that?” he will ask, and I will scramble to come up with an answer (a lie), to placate him before changing the subject. The bad man becomes simply a man. The police become simply protectors. I soften the edges, blur the facts, change the story, because for now I still can.

I know it won’t be long until he can read the headlines atop the photographs before I can bury the truth. My vain attempt to save him from the pain of the world can only last for so long. He will learn to read, and then to suffer. Words will haunt him. Stories will crush him.

He reads his first book, full of simple three syllable words, all by himself. I’m brimming with pride and terrified all at once.

I am starting to realize how much I lie to him—how often I find it necessary to shield him from the harsh truths of the world. I wonder if I’m doing the right thing by hiding reality behind this shimmering veil of half-truths. I want to extend the age of innocence as long as I can, but soon a day will come when I can no longer lie to him about the headlines and images he sees in the news. When he asks, "What's that?" the answers will no longer be as simple as an alligator, a man, someone who is sad.

I find myself wondering how I will ever explain away the horror stitched into the patchwork of our unfolding history. I ache with helplessness knowing how his fragile heart will break time and time again, just like my own. How is a heart that small supposed to hold all the pain that the world has to offer?

I’m not sure how I will teach my son about the parts of humanity I am still grappling with myself. I’ve had decades to learn how to cope with the hard questions, and I still come up empty on answers more often than not. How does injustice live so long and so prosperously? How can evil stand so confidently? Why do the same horrible things happen over and over again?

I don’t know. I don’t think I ever will. So perhaps the best I can hope for is not to spare him from the inevitable pain, but simply to hold his hand and say, “I feel it too.” Perhaps it is best to let him know it breaks me down too, that even I am not immune to feeling helpless and hopeless.

The truth is, I can’t spare my children from the dark side of humanity forever. But I can stand beside them and let them know I see it too, I feel it too, I want to change it too. I can let them know they are not alone. In the face of heart-wrenching uncertainty and tragedy, perhaps that is the best thing anyone can offer.